The Orthodox Barber

or, What Tools Shouldn't Be Used For

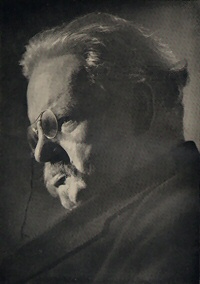

A little while ago, I dreamed I was back in the Edwardian-age London of 1909, discussing progress in our respective fields with a barber. I mused over an essay by G.K. Chesterton about the odd new fashion for gadgets at that time.

I had been invited to some At Home to meet the Colonial Premiers, and lest I should be mistaken for some partly reformed bush-ranger out of the interior of Australia I went into a shop to get shaved. While I was undergoing the torture the man said to me

"There seems to be a lot in the papers about this new shaving, sir. It seems you can shave yourself with anything with a stick or a stone or a pole or a poker" (here I began for the first time to detect a sarcastic intonation) "or a shovel or a"

Here he hesitated for a word, and I, although I knew nothing about the matter, helped him out with suggestions in the same rhetorical vein.

"Or a button-hook," I said, "or a blunderbuss or a battering-ram or a piston-rod"

He resumed, refreshed with this assistance, "Or a curtain-rod or a candle-stick or a"

"Cow-catcher," I suggested eagerly, and we continued in this ecstatic duet for some time. Then I asked him what it was all about, and he told me. He explained the thing eloquently and at length.

"The funny part of it is," he said, "that the thing isn't new at all. It's been talked about ever since I was a boy, and long before. There was always a notion that the razor might be done without somehow. But none of those schemes ever came to anything; and I don't believe myself that this will."

"Why, as to that," I said, rising slowly from the chair and trying to put on my coat inside out, "I don't know how it may be in the case of you and your new shaving."

G. K. Chesterton, The Orthodox Barber, in Tremendous Trifles

But did you know, I said to the barber, there are people today who believe you can describe a complicated business like banking or telephony just by drawing some stick-men and some ovals on a chart, and joining them together with little coloured lines without so much as a word of explanation?

Or that they imagine that they can prepare the specifications of some complex new device entirely in the form of logical symbols or engineering diagrams, hundreds and hundreds of pages at a time, and ask the poor customer to form a contract on the basis of his meagre understanding of what the analysts and engineers supposed was a logical representation of what the customer himself had said that he wanted?

Can you imagine, I inquired of the barber, there are salesmen who live entirely by selling tools on the pretext that these will instantly solve all the problems of engineering a new product?

And that they find a ready market, because development projects are so busy with complying with quality standards and guidelines, with going to conferences and meetings to find out about all the latest labour-saving gadgets, with keeping up with fashions and trends, with submitting to audits and preparing progress reports, with publicity and marketing and public relations and brochures, that the overworked engineers cannot spare the time to evaluate the products before they buy, and that although the tools often cost many thousands of pounds and are not meant for fools, the engineers can hardly take a moment to learn how to use them, so that often the newly-purchased goods languish and gather dust on a shelf, or else the engineers make such a hash of the work with the unfamiliar tools, that they would have been better off without them?

Have you heard, I whispered in the barber's ear, that well-known engineers speak to packed conference halls about doing away with tiresome product plans and specifications, preferring to save time and money by rushing into development unaware of either the risks involved, or of the real needs of their clients?

The barber wiped the last traces of foam from his dreadfully sharp old-fashioned cut-throat razor, and replied that he had not heard of these things, but that he expected it was the way nowadays.

As I awoke, I thought I glimpsed the plump cheerful figure of G. K. Chesterton, winking at me through his monocle from the door.

© Ian Alexander 2001